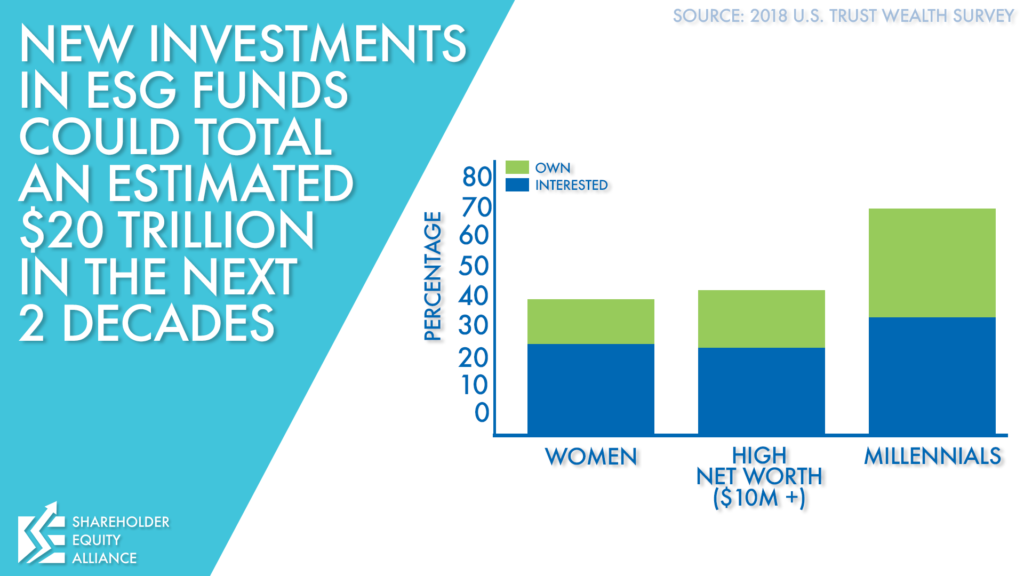

In modern investing, especially investing targeted towards millennials, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing is all the rage. ESG investing involves buying shares from companies with high ratings from at least one of the firms that rate companies on their “social responsibility.” Wealth management firms tell asset managers the best thing they can do is “tilt” portfolios to companies that prioritize high ESG ratings. They cite a “growing” body of evidence that suggests companies “doing good” also “do well” financially. Part of what’s driving this phenomenon is, as Black Diamond Wealth Management postulated, millennials are more likely to invest with ESG in mind. 95% of this demographic report that they want to consider their values in their investment decisions.

At first glance, it sounds like a win-win. Not only will we feel good about a company’s values, but since ESG funds do better financially than their non-ESG counterparts, our accounts swell at the same time.

But before shareholders rework their investment portfolio to prioritize ESG investing, it’s worth diving into an age-old question.

Which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Are companies with high ESG ratings profitable because of their focus on ESG? Or are companies first profitable and then incorporate ESG into their business models? Is ESG the cause of good fortune and accelerating stock value, or do responsible moral values merely follow good business?

Digging In

Let’s put aside for a moment that ESG ratings are not standardized, so what one rating agency considers a company “good on ESG,” another might consider “middling” or even “bad.” Even if ESG ratings were standard, at least a few of the regression analyses suggest that ESG is merely correlated with, not the reason for, a company’s financial success. This makes sense logically: companies whose products are flying off the shelves have money to spare to invest in values-oriented side projects.

A look at Fortune magazine unintentionally showcases this, too. By highlighting “5 stocks to buy for 2019,” the writer tells us to invest in Merck and Walmart because of their strong ESG values and financial success. But he offers no evidence that ESG values were the cause of Walmart’s or Merck’s financial success.

An implication like that doesn’t stand on its own. To make the case that Walmart has strong shares not because of its breadth of product offerings, or its dominance in rural areas, but because the corporation is a leader in reducing greenhouse gas emissions is certainly a statement that needs evidentiary support.

In fairness, the writer isn’t entirely clear. Perhaps he isn’t implying that ESG values are a reason for companies doing well. Perhaps he’s saying that customers should shop there, and stockholders own their shares, out of support for a “good” company.

But that doesn’t actually incentivize middling companies to integrate ESG into their companies to improve their bottom lines. It only incentivizes companies that are already excelling to dedicate revenue to social and environmental causes. If they advertise it in a PR campaign, they might add a few customers to their already-devoted customer base.

Reality Check

In reality, companies that “do well” do well because they sell things that meet a need in customers’ lives. Shareholders should invest in these companies because they believe in the utility of their products or services. It’s those products and services, not their values or moral responsibilities, that will improve customers’ lives.

It’s not a bad thing for companies to consider their social values, if it doesn’t impede the company’s shareholder value. But companies and investors alike have heard that companies with great ESG numbers have higher returns in their shares. That narrative is unsupported by facts.