Shareholder meetings, which the SEC requires annually, used to be a time to conduct real business. Shareholders and the board took on relatively mundane tasks. They ratified directors and audits, reviewed share ownership, discussed executive compensation, and the like. But while no one was looking, impact investors and political activists realized they could use this corner of the business world to their advantage. Slowly but surely, they began pushing companies to take actions outside their scope. Shareholder meetings went from a place of business-oriented tasks to one of unnecessary political statements.

Amazon: Change Over Time

Take Amazon as an example. While the company was wildly successful in 2010, in hindsight it was only the beginning. To see how they’ve changed over time, we compared their materials from the 2010 meeting to 2020. The difference is stark.

In 2010, Amazon’s proxy statement was 28 pages and covered business processes and procedures. They reviewed the ratification of the company’s independent auditor, discussed whether they should require disclosure of corporate political contributions, and considered share ownership and executive compensation. Ten years ago, there were only two shareholder proposals on the docket to review.

Fast forward to 2020, when Amazon’s proxy statement was 75 pages and contained 12 shareholder proposals to review. A majority of them were related to political causes. They considered environmental impact, immigration issues, gender and minority demographics, ideological discrimination, and social justice. Notably, most of these impact investors’ and activists’ proposals offered scant consideration of Amazon’s profitability or business model.

Only two of the 12 proposals were about something other than social, political or environmental initiatives. Those two business-focused proposals were:

- A proposal to decrease the threshold from 30% to 20% to call a special meeting (outside of the company’s annual meeting), and

- A proposal to require an independent chair of the board of directors, which would effectively remove Jeff Bezos as the Chair of the Board of Directors.

When Ideology Trumps Customer Service

It is a slippery slope when businesses feel they must make political statements or take stances on social issues. For example, Amazon joined the “We Are Still In” campaign after President Trump pulled out of the Paris Climate Accord. However, Amazon also gave funding to the Competitive Enterprise Institute, which disputes climate change science. Supporting both these efforts may help Amazon’s business: just because CEI has a different opinion on climate change doesn’t mean they don’t offer value in other ways. But climate activist groups like Majority Action don’t care about the nuance, or about Amazon’s business strategy. The fact that Amazon gives to CEI, even while supporting climate action, is enough to spark accusations of hypocrisy. Enough of those accusations might lead, for example, to a Twitter firestorm that causes Amazon to pull the plug on CEI — even if the relationship is good for their business.

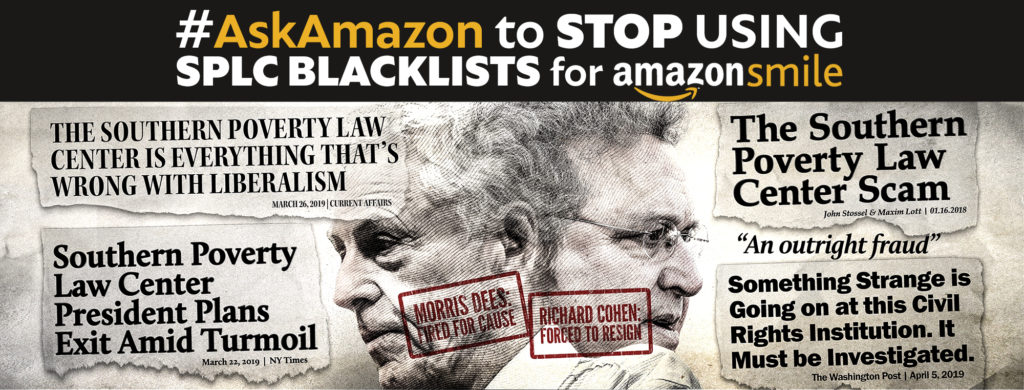

Additionally, Amazon has invited controversy with its AmazonSmile program. Amazon has contracted with the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) to decide which charities are eligible for inclusion on its platform. But SPLC is a known partisan organization, which has deemed mainstream Christian and conservative charities “hate groups.” It’s clear that in giving SPLC so much power over its charity selection, Amazon has tacitly, even if unintentionally, engaged in ideological discrimination against the views of many of its customers.

Better for Business

While philanthropy and community support in business is a good thing, it can also lead to reputational risk. Nonprofits that a company decides to support must jive with the campaigns that they back and whom they choose to do business with. If there are contradictions between a company’s policy and practice, it can quickly degrade stakeholder relationships and consumer trust. And if companies demonstrably care about impact investors than their customers, trust will degrade even more quickly.

As a society, it is critical that we allow businesses to do what they do best—business. When companies focus on short-term political or cultural whims, they ignore their primary responsibility: producing high quality products and maximizing the return on investment for their shareholders. Companies that focus exclusively on their core free-market missions don’t marginalize groups or individuals. And in doing so, they reduce risk and increase returns that benefit everyone.